A short history of Finnish festivals

Festival Fever – A short history of Finnish festivals from the early ages till 1990s

Kaija and Markku Valkonen, 1994

Edited by Kai Amberla and Minna Salonranta, 2013

-

1.The beginnings

Summer culture would have meant something rather vague to the city Finn of the 1950s: landing stages and dance pavilions, quiet holidays at the summer cottage, family get-togethers in pleasant but primitive surroundings.

No-one was likely to speak of “cultural summers”. The phrase was odd or – worse – old fashioned, inappropriate to the spirit of the streamlined Fifties.

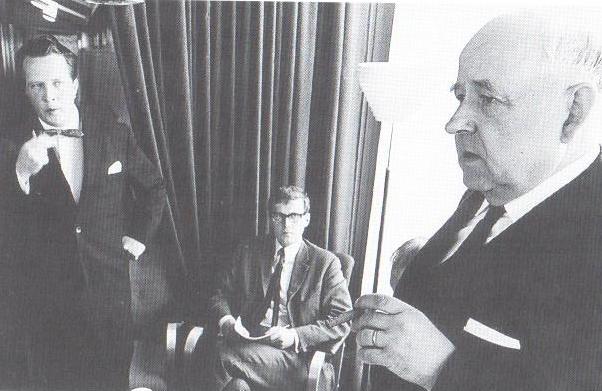

The energetic young composer and music critic Seppo Nummi (1932-81) thought otherwise. For him, “cultural summer” conjured up a marvellous vision of an unbroken chain of cultural events, calling a halt once and for all to summer’s sluggish indolence, uniting the arts and the light of the north in an ecstasy lasting all summer long.

Festival fever was already raging in Europe: Nummi counted over one hundred and fifty music festivals of various kinds. The desire and ability to travel had risen to new heights; the cultivated middle class desired stimulating content for their holidays. The triumph of recording techniques had merely served to increase the need for live music.

Journalist as he was, Nummi presented his idea in a column in Suomen Kuvalehti magazine in 1959: “In my mind, June and July would constitute a continuous two-month cultural event divided between five locations. The programme would follow the northward advance of the warm season. Helsinki and Turku would lead the way: Helsinki in early June, Turku immediately after the Sibelius Week. Savonlinna and Jyväskylä would follow on the dates already coordinated last summer: the Savonlinna music festival would occupy the last week of June and the first week of July, the Jyväskylä music and cultural festival the middle weeks of July. The series would culminate in an international music camp in Lapland, which would probably find particular sympathetic response among young Germans, hungry as they are for music and nature.”

The writer named his vision the Finland Festivals and suggested a loose-knit organization similar to the well-functioning one in the Netherlands. He challenged the other Nordic countries to a competition, suggesting an earlier date for the Sibelius Week: “The international stars making a solo tour of the north to the four Scandinavian music festivals would come here first, rather than last as they do now.”

Nummi dreamed of a grand future for the Turku music festival once an open-air stage could be set up in the courtyard of the restored medieval castle. Instruction was on his agenda for Savonlinna, with visiting teachers giving concerts to add diversity to the programme. The Jyväskylä musical and cultural festival would be expanded to a major event. “And Lapland will provide a magnificent finale to this summer symphony in five moments!”

-

2.From blissful backwater to cultural beehive

New as Seppo Nummi’s vision of a Finnish cultural summer was it sprang from home soil nonetheless. Behind it was the nationalistic cultural heritage of the 19th century.

The romantic, almost mystical idealization of the northern summer, of light and the midnight sun, was to be coupled with art of the highest quality available. The Finland Festival would be an event to rival any festival in Europe, while reflecting a distinctly Finnish characteristic: the complex, vital union of landscape and spirit. Finland would enter the Modern Era, and make sure that the rest of the world took notice.

In those days Finns were sensitive to criticism from foreigners (they may still be), as was amusingly shown in 1959, when a critic in Edinburgh wrote that Finland was a cultural backwater. Arvi Kivimaa, director of the National Theatre, grumbled that things could hardly be otherwise: “Finland has voluntarily, of her own free will, taken the stance that the rest of the world doesn’t need to know anything about us.” Nummi was horrified at the mere thought of a cultural vacuum.

Jean Sibelius, Alvar Aalto and the designers of the 1950s – Tapio Wirkkala, for example – were quite widely known in the world. To the annoyance of Finns, however, that was all. Nummi played his festival card with perfect timing, just when everyone else was running out of ideas. The spark caught fire immediately.

Seppo Nummi was a member of the Modernist generation, to whom the autonomy of the arts was all in all. His elder brother Lassi Nummi made his début as a poet in 1947; his eldest brother Yki Nummi was a designer. The Nummi home was a rendezvous for the cultural crème de la crème of Helsinki, and Seppo lapped it up to the very start.

Reminiscing about what his younger brother was like when still under school age. Lassi Nummi said: “Seppo liked to play at being Emperor, and was generous about handing out administrative work to us – our brother Yki was the commander of the army; if I remember rightly, I managed to secure the post of archbishop as well as the command of the Imperial Guard.”

Perhaps you have to be born with the talents of a festival director: maybe the spirit must be there before school and university smooth it out.

As a composer, Seppo Nummi got off to a head start. His songs were performed on the radio in 1948, when he was only sixteen. But why should a song composer and hardworking music critic devote himself heart and soul to organizing the county’s cultural world? Lassi Nummi believes that the choice was above all due to his brother’s social nature, his ‘greed for people’.

Viewed from a greater distance, one has the impression that Seppo Nummi wished to recreate the family and intellectual circle of his youth, but on the national – or, preferably, on the global – scale.

The young organizer may also have had the soul of an educator. He had no qualms about evoking the somewhat antiquated idea of ‘civic education’ even as an angry young Modernist. In the article “The idea of chamber music” (Uusi Suomi, December 16, 1955) he wrote about civic education in something like 19th-century spirit: “Music is sadly neglected in our civic education at present. Somewhat paradoxically, but adhering strictly to the truth, I claim that there can hardly be any more effective tool for social education than music. The wonderful treasury of chamber music passes down to us the most refined profundity of Western music, teaching us to hear ‘voices intimae’ and at the same time to feel a perfect, harmonious solidarity with humanity. Let this article contribute to the discussion of the past autumn concerning the significance of music to the totality of our society.”

-

3.Finland arise, Jyväskylä is coming!

Eloquent, quick-witted and uninhibited about showing off his broad knowledge of culture, Seppo Nummi had the chance to prove his mettle when he was appointed programme director of the Jyväskylä music and cultural festival in 1957. In his hands, the event in the capital of Central Finland developed into an ambitious summer carnival of the arts, with room for Karlheinz Scockhausen and modern Finnish poets, noisy debate and intimate chamber music.

In the’60s, the Jyväskylä festival developed into a forum for eagerly awaited debates and a testing ground for the pluralist ideal. The baby-boom generation had reached the age of awareness and sought new directions based on international trends, disclaiming the cramped outlook of the war generation and the reconstruction period.

The spread of television boosted the success of the Jyväskylä Summer Festival. The age of images and ‘talking heads’ had dawned. The dignity of consensus gave way to a whirl of dissension. No holds were barred in Jyväskylä: cultural prophets from around the world were invited to speak there.

Who would have dared to suggest that the sprouts of the new, unruly festival may have sprung from the same soil as all the decrepit old national and patriotic festivities, the defunct song festivals, the celebrations of rifle clubs and fire brigades, the provincial feasts and the student unions’ summer happenings?

Present-day festival visitors do not hesitate to admit that they particularly enjoy the ambience of the festivals. Spirit and emotion, the quest for community feeling – these, after all, were the goals of the old song festivals. Labels come and go, primal needs remain.

-

4.Resistance in song

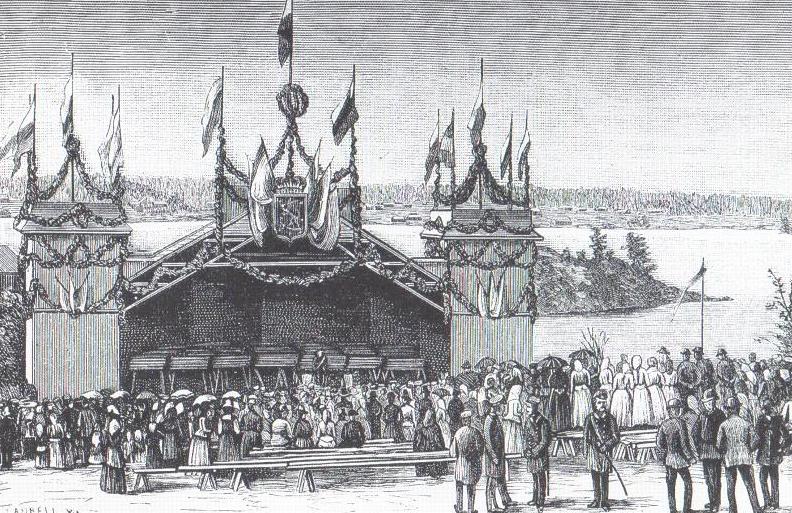

The modern music festival is a relatively new kind of event in Europe. Its origins seem to go back to church music. The charity service at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London was extended in the late 17th century to last several days, giving rise to a festival of music and choral singing named the Festival of the Songs of the Clergy.

The English were delighted with Handel’s oratorios. Choirs rehearsed them, and as much as three hundred singers and almost as many instrumentalists took part in the grand Handel festival at the end of the 18th century. Various choral societies were also set up on the Continent.

Switzerland evolved into a centre of choral singing. “The male voice chorus: a national strength”, declared Hans Georg Nägeli, a musician who had embraced the educational principles of Pestalozzi and believed, in the spirit of Enlightenment philosophy and the French Revolution, that choral music develops man’s best inclinations. At the time, the power of choral singing was aimed against Napoleon’s occupation force. In 1825, the German-speaking Swiss arranged the country’s first song festival, where patriotic feeling ran high. Physical military skills were honed with gymnastic exercises.

The first public song festival in Germany took place in Wurzburg in 1845. The political programme of the next event, in Lubeck in 1847, was no longer concealed, with participants openly demanding the secession of Schleswig-Holstein from Denmark. The Danes, however, put down the ensuing rebellion.

The historian Aimo Halila has traced back another fixture of the early music festivals: the celebrations of marksmen’s clubs, which were somewhat like trade guilds. The first Pan-German marksmen’s festival was held in Gotha in 1861. The programme included music, gymnastics and contest in the noble sport of singing.

The Nuremberg festival of 1861 marked the grand culmination for choral music. Within the space of a few decades, the repertoire had grown and diversified tremendously. Edifying speeches were an essential ingredient of the events, as were song and composition contests. An era began during which the battle of wits gradually came to be as highly appreciated as military prowess.

-

5.The countdown begins

The Germans exported their song festivals to the Baltic countries, where the original patriotic spirit has survived, amazingly fresh, until the present day. The mammoth events offered a surreptitious channel for giving vent to suppressed national feelings during the years of Soviet rule.

Tallinn’s first song festival was arranged by the city’s German population in 1857. Three years later, the Latvian capital Riga hopped on the bandwagon.

The University of Tartu became the hub of the Estonian national movement in the 1860s. The organist and newspaper publisher Johan Voldemar Jannsen (1819-1899) founded the Vanemuinen choral society, giving the wealthy ruling class of the Baltic countries, which liked to emphasize its German origins, a dose of their own medicine. The first Estonian song festival was arranged in 1869 on the initiative of the Vanemuinen society. The event was carefully timed, and this was an anniversary year for the abolition of serfdom, celebrated all over Estonia with “festivals of joy and praise”. This obeisance to the reformist policies of Czar Alexander I was simultaneously an act of defiance to the German population, Estonia’s other power.

The patriotic festival soon took root in Estonia. One of the keys to success was Jannsen’s widely circulated newspaper. What could more clearly express the reciprocal benefits of mass events and mass media? The press wrote up the rousing gatherings, analysed them and aroused anticipation – fanning the flame in the process.

Before the opening of Tartu’s first song festival in 1869, the rumour of great happenings reached the north coast of the Gulf of Finland. C. G. Swan and J. R. Aspelin (later State archaeologist), rushed to the festival. Swan wrote a report for the Finnish papers which changed the life of A. A. Granfelt (1846-1919), who was just over twenty.

“I was only a young student at the time, but I began to dream of a time when the two main tribes of the Finnic people would again draw closer to one another, and the Gulf of Finland, which now separates them, would be a link between them instead”, Granfelt later wrote.

He studied in Tartu in 1874, but the idea of the song festival lay dormant just then. In 1877, the time was ripe for a fresh starts. A number of Finns, cives academici Granfelt among them, were ready to attend, but the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish war postponed the event, and the new dates did not suit Granfelt. He had become a powerful official in Finland: secretary of the Kansanvalistusseura, the Society for Culture and Education.

The next song festival was arranged in Tallinn in 1880. This time Granfelt was in luck. He was able to attend, though the whole event was on the brink of cancellation. The Empress of Russia died on June 3, and the nation went into mourning with the Czar. Nonetheless, permission for the festival was granted. From this moment the countdown for Finnish festivals began.

-

6.“Finnish flags fluttered joyfully in the evening breeze”

After returning from Tallinn, Granfelt set out to find out how many choral and orchestral societies there were in Finland. Everyone who was someone was invited to the musical gala meeting of the Society for Culture and Education in Jyväskylä. The date was set for summer 1881.

Negotiations with Nestori Järvinen, religion teacher at the Jyväskylä Seminary, and E. A. Hagfors, the school’s music teacher, were marked by perfect harmony. Uno Cygnaeus (1810-88), head of the National Board of Education, was sour, however, predicting: “You and your festival: all you’ll get for your pains is a fiasco!”

In the 19th century, civic assemblies always entailed political risk and trouble with the authorities. Nor could anyone be sure when drunken pandemonium would break loose. Granfelt was a temperance advocate, and it was no doubt largely his doing that no alcoholic beverages were ever served at the song festivals of the Society of Culture and Education. “Moderate indulgence is the mother of excess”, he declared.

In the early 19th century, the main groups to sing in the streets were students. Even their activity was watched closely, as music – the most emotional and abstract art – could be used as a channel for radical patriotism. Not only the authorities but religious leaders as well looked askance at song festivals, considering them a frivolous abuse of leisure time.

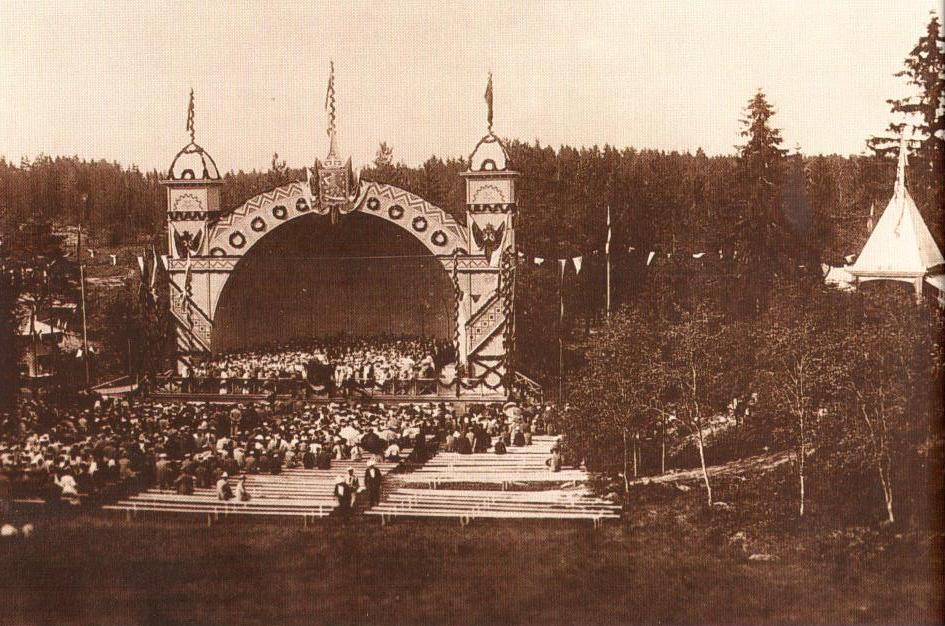

Granfelt’s festival plan was carried out, though in a format somewhat reduced from his original intention. The Society’s platform was raised on Jyväskylä ridge, and at 7 a.m. on Saturday, June 1881 the ceremony opened in an orderly manner.

The speakers could not forbear some paternal admonitions to the public. Agathon Meurman, the leading light of the “Fennoman” movement, which preached a national awakening, hoped that the organizing society would teach the people to celebrate in a way “apt to elevate the mind and to prevent it from sinking into the indecency which has so often brought discredit to folk amusements”. Does one hear echoes of his speech in the discussion of the behaviour of the rock generation on the grass of Ruissalo one hundred years later?

Despite the odd discordant note, the song festivals burst into full bloom in the 1890s. The closer the watch kept by the Russians on activities threatening the unity of the Empire, the more vehement the defensive posture assumed by Finnish culture.

During the ‘Russification’ of Finland during the early years of this century, the song festivals came under particularly heavy surveillance. Governor-General Nikolai Bobrikoff (1839-1904) banned large-scale public events in 1901, but Finns stubbornly kept arranging local festivities under the title of ‘summer festivals’.

Control was fairly slack, after all, as a reminiscence of the author F. E. Sillanpää (1888-1964) indicates. At the Kyröskoski song festival in 1904, the news that the hated Bobrikoff had been assassinated spread like wildfire. The celebrations continued, as Sillanpää described: “Finnish flags fluttered joyfully in the evening breeze, though ‘Poprikoffi’ lay on a stretcher in Helsinki. It was all so very liberal.”

In 1905, song festivals were again permitted. Bobrikoff was dead.

-

7.Separated by song, united by song

Civic education was promoted in various ways in 19th-century Finland. Well-meaning gentlefolk advocated the equality of all citizens. As historian Henrik Stenius points out, however, despite good intentions, class distinctions often proved insuperable. When singing and dancing were involved, the gentry would not readily submit to contact with the proletariat. They thought the smell of the vulgar crowd offensive, they feared vermin, and they suspected that all working-class women were of easy virtue.

A.E. Taipale, a voice teacher and choir leader from Pori, gave an account of how the National Chorus of Pori, which he directed, was on the verge of being disbanded in the 1890s. A young woman applied to join, and Taipale accepted her. The fine ladies of the chorus rose up in arms, however, declaring that they refused to sing by the side of a woman who worked as a public sauna bath. The sauna was a reputable establishment, but the director was forced to retract his acceptance of the woman’s application. She sued, and Taipale was fined sixty marks.

The choruses and bands of voluntary fire brigades were more successful than others in establishing harmony between the classes. By the 1870s some fifteen percent of their members were students, and the class boundaries were gradually eroded.

In addition to class distinctions, Finland was split in two along language lines. The Swedish-speakers wanted a song festival of their own; to them, the ‘Fennoman’ manifesto of ‘One nation, one language’ was unacceptable. Some bilingual summer events were arranged, the last major effort being the Vaasa song festival, at which all the leading Finnish composers, from Robert Kajanus to Jean Sibelius and Armas Järnefelt, personally conducted their own works.

Art was included on the agenda after heated debate within the Society for Culture and Education in the 1890s concerning the need for additional programming. Solemn processions, historical tableaux, flags, armorial bearings and garlands built up visual impact. The industrial town of Tampere even included a sensational marksmanship contest in its 1888 festival. Weightlifting and running events were also started.

In the bilingual celebrations at the end of the 19th century, the blue-and-white colours were still favoured, but later Finnish and Swedish-language events sought to set their own visual tone. The Swedish-speakers favoured red and yellow; their favourite symbols were the lyre and the island landscape. The standard emblems of the Finnish-speakers were the Maid of Finland, the kantele (a traditional Finnish string instrument) and the lake landscape.

National costumes were in vogue at all festivals. Especially among the bourgeoisie, they were not merely party wear but symbolized the rising regionalist spirit. The costume instantly expressed the group, tribe or locality with which its bearer wished to be identified. Thus, the song festivals both united and separated the nation.

-

8.A sad but efficient nation

“If several talented and witty people meet, all they need to do to amuse themselves is open their mouths; if several serious and ungraceful people meet, they must organize an entertainment. Amusement is a necessity, and if it does not arise by itself, our will fills in the gap with artificial entertainments. Therefore the peoples who lack the inclination or the sense of humour to amuse themselves naturally are the ones with the best and most varied theatrical performances. Through its organizing ability, the Finnish nation, which is one of the saddest in the world, paradoxically turns into one of the world’s most joyful and entertaining nations.” thus wrote in the Granada newspaper El Defensor the Spanish consul and writer Angel Gavinet y Garcia, who sent home a series of travel descriptions from Finland in the years 1896-1898.

Perhaps Gavinet was not too far from the truth? At any rate, he had experienced, perhaps without realizing it, a significant economic and cultural boom period in Finnish history. Many a seed germinated and the Finnish outlook widened in the last years of the 19th century, despite – or perhaps because of – harassment from the expansionist Pan-Slavic movement in Russia. No wonder that the Finns had developed into a nation of festivals: there was a demand for ideological celebrations.

What is more, the economic base was there. Trade had been liberalized and the guild system abolished. Capital began to move when joint-stock companies were legalized in 1864. The next year, the Czar granted the Grand Duchy of Finland the right to issue its own currency, giving Senator Johan Vilhelm Snellman (1806-81) one of the greatest victories of his political career.

At least as important was the success of Snellman’s cultural programme. The Finns increasingly put faith in his idea that culture is the strength of a small nation, equated with patriotism.

The rural landowners grew rich as the rise of the sawmill and papermaking industries increased the value of forests. Communications improved: the Helsinki – St. Petersburg railway opened in 1870, shipping was promoted. The statistics for the 1890s reveal a momentous change: Finland had less trade with the mother country Russia, than with Germany. The economic upswing was backed up by the introduction of a national education system. Finland had 146 elementary schools in the early 1870s; by the turn of the century, there were two thousand.

Money, time and creative energy were invested into international public relations. One of the notable cultural projects of the period was the Finnish pavilion at the 1900 World Fair in Paris. Finland had gone international.

Finland in the 19th-century was a promising land of associations as well as of festivals. The national temperance movement strengthened its grip and called for social reform. Other mass organizations followed suit – workers’ organizations, women’s organizations, agricultural societies, and above all the youth association movement, which developed into an influential education force in theatre and singing. New choral societies sprang up everywhere. In fact, Henrik Stenius believes that choral singing, with its far-reaching organizational aspects, was the most important form of aesthetic expression at the time.

The Spanish consul Ganivet noted: “There is a great vogue for music and talent is aided; yet there are no composers of stature apart from Pacius, who is a second-class figure.”

The Finn is quick to growl: “And what about Sibelius, señor Gavinet?”

Perhaps our Spanish informant had the same attitude to Jean Sibelius as to Akseli Gallen-Kallela, a painter “whose imagination and ability are somewhat disordered”.

But had the right honourable consul ever heard of K. G. Streng, the parson of Lemi, who in the 1850s had trained his entire congregation to sing in four-part harmony? It is said that the farmers went around with a tuning fork in the leg of one boot, and at home families practiced their voice parts to the accompaniment of the kantele.

-

9.Let us singers inspire one another with song

In the late 19th century, the cultural organizers found their strongest support among the wealthy landowners in the rural areas. Prosperous country folk allied themselves in the name of the fatherland with the educated classes of the cities. Official cultural policy became the domain of the bourgeoisie, though serious efforts were made to bridge the social gap in many projects.

The gap between festival addresses and reality, between the landless and the landed population, widened further; labour began to feel its strength and organize. Soon new choral songs echoed in the workers’ clubs. As if unawares, the country had divided into two camps, the propertied class and the workers, the political right and the left. This ominous development came to a head when civil war broke out in 1918.

After the civil war, most workers’ choruses no longer took part in the song festivals of the Society for Culture and Education, at which the ‘tribal ideology’ of a union of all peoples speaking Finnic languages was urged, sometimes quite aggressively. A consciously militant tone was set at the Sortavala song festival of 1924. President Lauri Kristian Relander attended together with the Minister of Defence and the Commander of the Armed Forces. The principal speaker, writer Artturi Leinonen, blustered: “Does anyone catch a whiff of the dream of Greater Finland, a dream supposed to be buried and forgotten? It will never be forgotten!”

The workers’ faith in the power of song was just as unshakeable as that of the middle class. Evert Konttinen wrote in Työn Sävel (The Melody of Labour) in 1921: “Let us singers inspire one another and the entire suffering working class with song to an ever sterner struggle against the capitalist society, built on oppression and injustice. Our motto: “The art of song to the workers!”

-

10.The friction between high art and amateurism

The friction between amateur and professional, folklore and foreign influence has always chafed festivals of music and culture. At the song festivals of yore, the conflict brewed for years, until Heikki Klemetti, one of the key figures of the Finnish music world, resolved the problem in one fell swoop. Disgusted with the performances he had heard at the Viipuri song festival in 1908, he stormed in his inimitable style:

“Still the same performances, ignorant of all singing technique, fumbling in the darkness of incertitude; the same lack of consistent, natural phrasing; false notes; a tasteless selection of songs. What in God’s name is the use of these great annual goings-on, this dreadful din and braying of brass, if we are never to rise above this musical vale of tears?”

Klemetti led the Finnish choral movement to a new rise. A keen-eared, vigorous, truculent individual like him was no doubt needed for the project. The story goes that the Ostrobothnian master suffered from musical discord so much that he could not bear to listen to birdsong – the birds in his yard were in the habit of warbling out of tune.

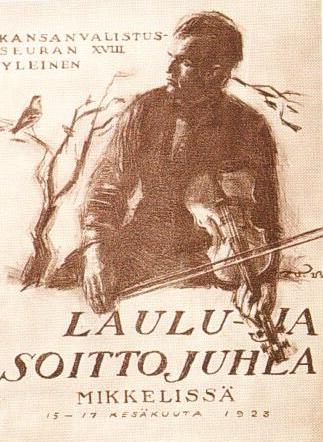

The Society of Culture and Education gave up its role as chief organizer of song festivals when Klemetti took over the directorship of the Choral Association in 1929, and was enlarged in the early 1930s to form the Finnish Amateur Music Association. The new organization arranged its first choral festival in 1934.

The swansong of the old type of festival was the Kalevala centenary celebration in 1935. The entire Finnish elite graced the principal event (in Helsinki’s Fair Hall) with its presence. The other main venue was the town of Sortavala on Lake Ladoga (ceded to Russia after the Second World War), where a rune-singer’s statue by Alpo Sailo was unveiled with pomp and circumstance. Kyösti Kallio, then Speaker of Parliament and later President, gave the keynote address. The musical climaxes of the event were a performance of Erkki Melartin’s opera Aino and a concert by the Helsinki City Orchestra.

-

11.The first opera performances in Savonlinna

The song festival of the Society for Culture and Education would not have been possible without the rural tradition of neighbourly help. Many a present-day festival depends on this very spirit. Still, an imposing setting could not be provided without tickets sales. In the early years, tidy sums flowed into the coffers of the Society for Culture and Education, but things changed after the Viipuri event in 1908.

A.A. Granfelt wrote dejectedly:

“Since then, song festivals have no longer been a source of income for the Society. The arrangements were more splendid than ever, fortunes were spent on festival processions, opera and oratorio performances and other, mainly artistic, endeavours. This left nothing for the Society, which in fact had to make gigantic efforts to cover the deficits which arose from the festivals.”

The present-day festival organizer cannot help feeling sympathetic – Granfelt, if anyone, was genuinely a colleague and fellow sufferer.

Idealism, money and endless voluntary work was also needed in introducing a more specialized kind of festival. Our internationally most successful opera star, Aino Ackté (1876-1944) had the idea of arranging an opera festival in the courtyard of the mediaeval fortress of Olavinlinna in summer 1907. The plan met with difficulties, as one might expect; not even the Society for Culture and Education backed it. Pentti Savolainen has speculated that the reason was Heikki Klemetti’s aversion for the ‘elitist’ art form; Klemetti was a member of the Society’s committee charged with modernizing the content of the song festivals and rising their artistic standard.

Ackté went on planning her festival, unperturbed. She had discovered that the castle courtyard had good acoustics, space for sufficient number of seats, and could be covered with a canopy in the event of rain. Electricity could be provided by running a cable from the adjacent town of Savonlinna along the lake bottom.

Ackté’s realistic view of the potential public was the crux of the matter. The local population would not fill up the seats, nor would Finns from other parts of the country. The regular boat service between Savonlinna and St. Petersburg, however, would bring the upper classes of the Russian capital to the festival: the border, after all, was open.

Ackté was accustomed to the world’s grand opera stages, and her visions extended far beyond the Finnish borders. In her mind’s eye, she saw a spectacular festival in the castle that would enchant foreigners and gather sympathy and friends for Finland. Every summer she would stage a new Finnish opera, starting with Melartin’s Aino. Ackté’s idea sprang directly from the cultural policy devised by Finns during the first period of Russian oppression: they felt that they must become international in all fields in order to preserve their national autonomy.

The first Savonlinna festival opened on July 3, 1912 in favourable weather. Ackté, who sang the lead role in Aino, reported that the opera was performed “to the accompaniment of the birds of the air”.

Oskar Merikanto, the festival’s general director and factotum, noted “the devoutness with which simply country men and women followed the performance”. Thus, the public did not consist exclusively of gentlefolk and foreign tourists, although many a fine lady had a shock when asked to remove her wide-brimmed hat before the performance. How many pins had been needed to fasten it in place!

The Savonlinna Opera Festival never would have got off the ground without a highly developed musical foundation. The major Finnish towns had orchestras and a lively concert season; nor was opera by any means unknown. The Finnish Theatre, founded by Kaarlo Bergbom, had had an opera section since the 1870s, though the first fully-fledged opera company, the Finnish National Opera, was not founded until 1911.

The cultural historian Hertta Tirronen pointed out that by the time that Finland gained independence (1917), the country had general music culture which most citizens, regardless of social status or education, recognized as their own. Popular art music and folk melodies were especially widespread. Operetta and opera tunes, marches, waltzes and folk songs could be heard in concert halls and parks at social entertainments and skating rinks.

Music had happened since Finland had been annexed by Russia in 1809, a time when art music could be heard mainly at country estates and parsonages, and the gentry spent their time “conversing, botanizing and musicking”.

Aino Ackté arranged four one-week opera festivals in Savonlinna between 1912 and 1916. Only once did she succeed in reviving the event, in the summer of 1930. This attempt came during the great depression, also a time of sharp political divisions. The organizers ran out of money, and the 1930 opera festival was the last in 37 years.

The festival director’s life is no bed of roses, as Aino Ackté too found out, for envious eyes see enormous riches even where the coffers are empty. It was rumoured that Ackté had used the festival for her own financial gain, though in fact she had quietly invested a considerable part of her own savings into the event.

-

12.Land of farmers, culture of cities

In 1929, the Finnish Broadcasting Company – which had been founded three years earlier – made a survey of its listener’s preferences. Most of them wanted to hear comic songs, accordion playing, brass bands, folk song, radio plays and cosy chats. Solo female singing, opera and operetta, language instruction, symphony music and jazz were abhorred. Listeners wanted practical information but set little store by philosophy or art.

The wireless was one of the main propagators of Finnish unity after the divisive civil war. The modern appliance disseminated the values of a new, technological world and loosened up the traditional high-mindedness of popular education. Entertainment had come to stay.

The depression of the Nineteen thirties was followed by an economic boom. Finland revived. Social conflicts were no longer quite so pointed, although “in Finland liberals, radicals, radical literary movements, pacifism, psychoanalysis, the League of Nations, modern literature and the Scandinavian orientation are all counted semi-communists”, as a radical reeled off in the Pidot Tornissa symposium book in 1937.

Finland liked to compare itself with the Scandinavian countries, sometimes forgetting that it was a much more predominantly agricultural society than its neighbours. The Scandinavian orientation became official foreign policy in 1935, a sign that Finland wished to reject national socialism and remain democratic. Nevertheless, German culture was prevalent. Academic Bookshop in Helsinki ranked fifth among all European bookshops in sales of German literature.

-

13.Modernism – but that’s already been invented!

The course was completely reversed after the war. Finns turned particularly towards Anglo-Saxon culture. They struggled to shed anti-Soviet attitudes and to build up relations with the great neighbour in the east. Germany was sidelined.

The last trainload of war reparations was sent off to the Soviet Union in 1952, completing the delivery of three hundred million gold dollars’ worth of goods to the victor. The reparations were harsh, but they speeded up Finland’s development. As the 1950s opened, Finland was no crushed beggar but an increasingly prosperous industrial state ready to face the future.

The metamorphosis was complete. A new generation took centre stage, giving short shrift to old formulas. The success of Finnish designers at the Milan triennials raised Finnish self-confidence, and the objects they made were symbolic change: the streamlined vase on the table or the cloak like an abstract painting over the shoulders reflected a new way of thinking. Architects drew visions of a modern utopia, which began to materialize. Nonfigurative art gained ground despite the growls of the older generation and the suspicions of the public. Rhyme and fixed metre disappeared almost entirely from poetry.

The itch for modernity was irresistible, though its progress was not always smooth. The composer Einojuhani Rautavaara (b. 1928) recalls from his student days in the 1950s: “Incredible as it seems, I seriously believed that I had invented keyboard symmetry as a technique of composition in the years that I composed the Three Symmetrical Preludes and even played the at the Jeunesse Musicale festival in Bayreuth. In fact I did invent it, as I didn’t know of any precedent. Not until attending lectures on new music at the Juilliard did I discover that others had been there before.”

Modernism – perhaps it had already been invented elsewhere?

-

14.Throw out the mothballs!

In the 1960s, the economy grew apace. Leisure time increased: Finns now got Saturdays off as well as their long summer holiday. Almost every household had a car. Foreign tourists arrived in increasing numbers, but found little more than natural beauty and summer somnolence. Finland was in wraps.

This drowsiness did not suit the zesty spirit of the Sixties. Many felt that something more dynamic was called for, and post-war modernization was completed: the mothballs were thrown out and Finland was dragged into a new age. Whereas the ‘50s generation had kept at arm’ length from politics, the new politicized generation invoked the support of the people, demonstrated and sang.

A particular source of amusement for this generation was whenever it succeeded in provoking some ‘reactionary’ figure. A real treasure in this respect was the ‘strong man’ of the Jyväskylä Summer Festival, Päivö Oksala, professor of Classical literature. He played his conservative role with the flair of a born actor, pulling out the microphone cables or darkening the whole auditorium when the blasphemy went beyond his endurance. The media loved him.

The leaders of the country, President Urho Kekkonen above all, realized what a useful tool the new political radicalism could be turned into. And so it happened that what divided nations elsewhere united Finland. The open wounds of the civil war were healed.

The overhaul in music education was less dramatic but even more effective: numerous new music institutes and conservatories sprang up throughout Finland in the course of the ‘60s, many in small towns. Music education was vigorously decentralized, and the fruits of this work have gradually matured. The results look good.

-

15.Finland Festivals is born

Finland in the throes of change needed new, stimulating forms of togetherness to strengthen the regained sense of community – a new Granfelt to impress the need for culture on people’s minds. Such people were at hand. Their kingpin was Seppo Nummi.

Seppo Nummi left Jyväskylä in 1968 to direct the summer festivals of the Helsinki Foundation, which had been set up a couple of years earlier. The idea was to awaken the capital’s drowsy summer season to new cultural life.

The Helsinki Festival filled in the vacuum left by the Sibelius Week, an event that had lingered on for fourteen summers, elegant but anaemic. According to Nummi, its problem had been the smallness of the targeted public coupled with unimaginative programming based mainly on the works of Sibelius. National hero worship was no longer the order of the day.

Almost unawares, the summer season had swelled into a steady stream of events during the ‘60s. Savonlinna offered concerts as well as opera; Turku had summer festival of the local musical society; the jazz fans had discovered Pori and Kirjurinluoto; Orivesi’s Klemetti Institute had offered summer concerts since the ‘50s; Vaasa was tuning into cultural debates in the Jyväskylä spirit.

Had the cultural summer envisioned by Seppo Nummi in 1959 come true? This had not happened quite spontaneously – the ubiquitous Nummi had been involved in the planning of most of the festivals. At any rate, there was now enough going on in the Finnish summer for Nummi to be summoned to draft an overall strategy. A plan for the jigsaw puzzle of information, marketing and timing had existed for ten years; it only awaited realization. Finland Festivals was entered in the company register on December 28, 1968.

The first, four-page annual report states:

“Finland Festivals was founded in Turku on June 12, 1968 to act as coordinator between the organizers of music festivals and cultural events and thereby to promote familiarity with these events at home and abroad. The signatories were the Helsinki Week Foundation, the Turku Musical Society, the Jyväskylä Cultural Festivals, Pori Jazz ’66 and the Savonlinna Opera Festival committee.”

The first chairman of the new association’s Board was Viljo Virtanen of the Savonlinna Opera Festival, and Päivö Oksala of the Jyväskylä Arts Festivals was vice-chairman. The members were Viggo Groundstroem (Helsinki Festival), Olavi Sarmio (Turku Festival), Tapani Kontula (Pori Jazz Festival) and Henry Lönnfors (Vaasa Summer Festival).

The Tampere Theatre Festival and the Kaustinen Folk Music Festival were invited to become members during the first year. The board decided to accept the Vaasa Summer Festival as soon as it had the appropriate organization.

The board recorded the following decision in principle: “The membership of Finland Festivals (8) will not be increased without specially pressing cause, such as an appropriate festival set up in northern Finland.”

The board had to eat its words the very next years. The Kuopio Dance Festival was accepted as a member, and again it was agreed that the membership would not be increased without special cause – such as “a cultural event established in northern Finland in harmony with the association’s principles”.

-

16.The idea catches on

Finland Festivals was already in action before it was incorporated. The joint brochure for the summer 1968 still appealed to the old standbys of Finland as a land of architecture and design. The next year was a time of jubilation as the arts had been in the Finnish summer, the ice had now thawed and summer culture had burst into flower. There was some substantiation for this claim: total attendance was over one hundred thousand. To be sure, this actual number of festival visitors was much smaller: attendance was computed by adding up the number of tickets sold to the various events; many festivals even counted the spectators of events for which no admission was charged. In 1970 attendance rose to 150,000. The most popular event was the Tampere Theatre Festivals, with 37,156 visits; the Helsinki Festival came close second with an attendance of 35,224. “The results can be considered encouraging for the Finland Festivals organization, too.” the Board reported.

And then?

“The total number of visitors surpassed even the boldest expectations, and the outcome is virtually unparalleled after such a short period of operation.” There had been 425,000 visitors.

Amid jubilation in 1971, the Finnish cultural summer was proclaimed unique in the Nordic countries. Attendance had risen again – to 600,000. “The result can be considered excellent”, as the annual report modestly put it.

The half million line had been surpassed, and audiences grew from year to year. In 1979, the member festivals had an attendance of 800,000. If the new ‘recommended events’ were included, the figure already exceeded one million. The sky seemed the limit.

Seppo Nummi was radiant: “Never again will we be equated with reindeer or polar bears. Even the trees in the forest are no longer our main magnet. We have something truly exceptional to offer our guests: the most up-to-date and international art scene in the midst of the most intact wilderness landscape in Europe, framed by the quiet and spaciousness of our summer.”

The PR campaigns had worked. The Finnish summer festivals had been written up in many countries, especially the United States, where the flag was held high by Tatu Tuohikorpi, press attaché at the time. In its supplement on forty European cultural events, the New York Times included eight Finnish events: Helsinki, Savonlinna, Jyväskylä, Pori, Turku, Tampere, Kaustinen and Vaasa. The impression given was that Finland provided one-fifth of Europe’s entire festival capacity.

Perhaps not all of these events were quite worthy of the attention of a paper of New York Times stature. When the Vaasa Summer opened in 1972, two spectators showed up in the Town Hall’s assembly hall. They quietly went out again to witness the raising of the festival flag.

-

17.The joyful festival visitor

If design was Finland’s ambassador in the ‘50s, it was now replaced by the summer cavalcade of festivals.

To be sure, our music festivals were not particularly unusual; there were many similar, much older events in Europe. What was exceptional was the large number and popularity, occasionally also the quality of the events. Another original feature was the coordinating organization, which was highly successful in disseminating information about the events and marketing them. Writing in the American Music Clubs Magazine in 1970, Pat Patricof could think of only one parallel: the Holland Festival. Holland had been in Nummi’s mind, too.

“An ensemble like this cannot be found anywhere else”, boasted Maj Nuortila, general secretary of Finland Festivals. According to her, Finland Festivals was a Finnish design product, and the key to its success was people’s growing workload during the winter. Unable to satisfy their need for culture in the winter, people made up for the deficit in summer.

Nuortila was appointed general secretary of Finland Festivals in July 1971. She was followed by Eeva-Liisa Tarvainen (1973), Marianne Kajaste (1975) and Arja Gothóni (1977). Matti-Jussi Pollari took over as executive director in 1982, Tuomo Tirkkonen in 1986, and Kai Amberla in 2007. Finland Festivals opened its first office at Unioninkatu 30, Helsinki in 1973.

Pat Patricof of Music Clubs Magazine was amazed at the spate of events in a part of the world that would hardly come to the mind of the average American in a cultural context. She thought the summer miracle could be explained by the fact that the enterprising Finns had always held education and intellectual pursuits in high esteem.

The Finnish press could not stop marvelling at the alacrity with which the Finnish people had accepted the festival idea. Nummi was not surprised; what puzzled him was why no-one had noticed before that the Finn truly comes alive in summer.

Finland’s leap from an agrarian society into the ranks of the industrial nations had left the urban middle class and especially its youth without summer rituals. They had to be fashioned anew: even society is afflicted by horror vacui, the terror of the void. The relaxed summer atmosphere allowed people to think and act a little more freely, to let their hair down. Nummi had intuitively understood the longing for new rituals. He was always eager to emphasize the social function of the festivals and the significance of a flexible, liberal organization.

“The festival visitor could be characterized as joyful”, Nummi said. Joyful or no, some festival gene must have lain hidden in the souls of the Finns since the days of the song festivals. Jouni Mykkänen, chairman of the Finland Festivals board, wrote in Aamulehti newspaper in 1982: “We Finns have an exceptionally strong need for summer culture. You don’t find the same enthusiasm in other Nordic countries, for instance. – It is partly a new way of seeing people and, of course, of satisfying a kind of cultural hunger at the same time.”

An anxious press warned readers against excessive optimism and predicted disaster year after year. Nummi countered in Uusi Suomi in January 1972: “There are many funeral quests after every summer: for a decade now, we have been told that this is only a fad that will soon die away. And yet the audiences keep on growing at a tremendous rate.”

He thought the festivals’ strengths were variety and geographical scattering:

“The specialities of the member festivals extend all the way from pop, political cabaret and jazz to experimental Modernism in the fields of architecture, design and chamber music; from ballet to symphony music; from the most ancient and solemn vintage in music to folk music performances and spectacular stating of opera in the Olavinlinna castle courtyard of amid the austerely impressive concrete structure of the Helsinki Ice Hall.”

-

18.Night frost bites cultural summer?

Judging by all the success, praise and growing audiences, one might think the work of the festival organizers was just one big party.

Far from it. Lack of funds threatened most festivals every year. The Savonlinna Opera Festival hovered on the brink of the precipice in 1972, and the Turku Festival was also in trouble. Savonlinna suffered from rains, which kept audiences away. Turku was menaced with the closing of Ruisrock, as the rock festival’s drunken audiences could not be kept in order. The worst of it was that money from rock fans largely kept the other concerts in Turku going.

Ticket sales covered part of the budget for nearly every event. Public support was indispensable: the State provided approximately one-third of the requisite funds. There was, of course, a constant squabbling over this kitty. The organizers vied with each other in asserting how cheaply they put up their events. Enthusiasm, voluntary effort and hospitality made up for small budgets.

“Art festivals must be watched over!”, the press – especially the left-wing papers – demanded, grumbling that the ordinary taxpayer had no place at the festivals. “Despite State subsidies, ticket prices are relatively high. Therefore the artistic experiences provided have already become virtually the exclusive right of the wealthy.”

The international energy crisis heightened the problem in the mid 1970s. Johannes Virolainen, chairman of the Centre Party, added fuel to the flame. “The fat years of the late 1960s and early ‘70s cannot be expected to return. – The good times for the Finnish people will never return”, he predicted in Uusi Suomi in August 1976.

The speaker was as good as his word: Finland Festivals received no State aid at all the following year. An Aamulehti headline in May 1977 ran: “Night frost bites cultural summer?”

Was this the end?

Maj Nuortila, bureau chief of the Helsinki Festival, proclaimed:

“Talk of the devil and he’s sure to appear. – The budget is two million marks. This may seem a lot, but if you compare it with that of the Edinburgh Festival, they spent this sum just on advertising.”

State subsidies were not the only grief. The tax bill of 1973 came close to killing off all festivals of international stature. A 30 per cent tax was to be withheld from the fees of all foreign artists.

“This is like a bad dream”, groaned Jyrki Kangas, director of the Pori Jazz Festival, and went on to demand a special exemption. “They exempted mother’s milk, too…” Matti-Jussi Pollari calculated that Finland would have to pay 60 per cent more than other Nordic countries for foreign performers. Kalevi Kivistö, chairman of the Finland Festivals board, estimated that fees would rise 82 per cent once the new legislation on artists’ pensions came into force.

Finland Festivals launched appeals and campaigns; the press took up arms on behalf of the festivals; a period of organ grinding was predicted for music unless the withholding tax was abandoned. A compromise was reached three years later. The subsidies for some festivals were raised enough to cover the cost of the tax.

The reverses met by the festivals had softened press criticism. Suomen Kuvalehti showered them with praise in a leader in summer 1978:

“The Finland of open-air dances, agricultural exhibitions and historical pageants has developed into a country of music – with a rich, varied cultural summer the value of which may not be fully understood yet. Many projects have been pruned for financial reasons. Public support has been scanty or nil. Still, one must remember that such proof of a nation’s culture cannot be bought with silver of gold…”

Still, silver and gold were also needed. In the early 1980s, the festivals entered a new age: they started seeking business sponsorship. The economy was thriving. A festival brochure from 1986 states: “The business world is increasingly realizing that a sound culture provides the best foundation for all economic activity…”

By the summer of 1993, Finland had come full circle. The Ministry of Education proposed that funding for the festivals could be experimentally guaranteed for several years at a time, permitting longer-term planning. In the eyes of the decision-makers, the cultural summer was no longer passing fad but an established part of Finnish life.

-

19.Home-grown or imported goods?

The will of the people, the good of the people, impartiality and equal rights were the banners under which the cultural debate of the 1970s was waged. Elitism was a four-letter word; popular culture and art sociology were in.

It was little short of a miracle that the Finnish festival summer – elitist as it was – survived these years virtually unscathed. Perhaps the spontaneity characteristic of the summer events, the heritage of the Jyväskylä spirit, ultimately silenced the critics.

“In art sociology terms, the summer events, untouched by senility, come out to meet their public,” as Seppo Nummi put it in the jargon of the new age. He described ways in which new forms of communication could be tested in the summer in order to reach age and social groups who had “been less in touch with the art world, but whose involvement is most desirable and important.” He also pointed out that the summer festivals sought to counterbalance the rather institutionalized character of culture at large.

This was all that was needed. The most elitist cultural aspirations of the time had struck the right note for the left wing. Nummi himself did not jump on the leftist bandwagon; he remained on the opposite side, styling himself a monarchist or a royalist.

The ‘elite festivals’ eventually found its severest critics among private citizens. Especially at the venues of the more ambitious festivals, angry voices were raised, demanding to know why expensive foreign performers had to be imported, when the local people, too, could sing and play music.

“We cannot help feeling that the festivals are arranged by a self-sufficient clique who look for praise elsewhere and money here”, Elina Juntunen wrote in Karjalainen in 1985. Her target was the Joensuu Song Festival, the principal venue of the Kalevala sesquicentennial. The writer complained that the common people felt sidelined in the high-calibre international music programme. “I cannot express my surprise that 33 productions should be brought to these ‘song lands’ from outside. Was there faith in our resources?”

The question was reasonable enough, though it was undermined by the writer’s own observation that North Karelia in those days could not boast of the excellence of its choral singing.

Kalevi Kalemaa wrote in Suomalainen kulttuurikesä (The Finnish cultural summer, 1974): “Generally the moving spirits behind these events do not bother to find out about the musical interests of the local people. The choice is made by some committee of outsiders, whose preferences the programme reflects.” Kalemaa did not call for a radical revision of programming but proposed a much more moderate recipe: concerts with programmes by popular request to be included in the festival.

In some places, culture and its peculiarities gave rise to moral indignation. Pirjo Nenola writes in her historical overview Aina täysillä (Full speed ahead, 1991):

“Some think the Iisalmi Camera Festival an elite event which devours taxpayers’ money without offering anything much to the local people in return. The festival has even been thought morally dubious, as models of the nude photography workshop have been observed at work on the roof of the cultural centre…”

Worst of all, however, was art that was incomprehensible. John Cage’s ‘paper bag concert’ in Viitasaari Church in 1983 raised such a storm that the new music festival, which had only just got off the ground, almost collapsed there and then. A petition for withdrawal of the festival subsidy from the municipal budget, initiated by disappointed concert-goers, went round from door to door. The organizers applied for 100,000 marks and received 50,000 from municipality. Executive director Veikko Korhonen surmised that Cage had been invited to Viitasaari too soon: people were not ready for him.

-

20.Finland Festivals – a matter of course

One of Finland Festivals’ first challenges was to link up it member festivals into a continuous chain of events. Even the slightest overlap gave rise to rancor, as the idea of the unbroken chain had become sacred. After four years, only Olavi Veistäjä complained because the Turku Music Festival overlapped with Tampere Theatre Festival on one day. He demanded that the Turku event should be removed entirely from the list. The Turku organizers replied that the Pori Jazz Festivals and the Savonlinna Opera Festival had frequently coincided, in perfect harmony.

In 1974, the last overlaps were removed. But this was not good enough, either. The next year, Seppo Nummi berated Finland Festivals for having “tinkered away with minor problems”, produced “a couple of distinguished joint brochures” and “wasted much time and tobacco” pondering a few questions of coordination in timing.

Nummi himself had more ambitious plans. “Finland Festivals should work ten times as hard with a budget measured in millions at selling the Finnish music summer to foreign tourists; the investment would come back tenfold in the form of currency.”

But the King of Festivals was running out of steam. Leaving the Helsinki Festival in 1977, he said in an interview in Ilta-Sanomat: “I feel as though the Finnish summer has squeezed out everything there is to squeeze from Finland’s summer festivals… I have sometimes thought that the quickest way to the sanatorium is to organize outdoor events in Finland and in summer.”

Nummi’s youthful vision had come true beyond his wildest dreams. The seeds sown by the major events had sprouted into a whole network of festivals. In the mid 1970s, over a thousand summer events were counted, from small-time village feasts to major international festivals.

The local celebration became a downright status symbol. If a town had no festival of its own, the question of why no international event had been arranged might be asked even in newspaper editorials. A columnist in Ilta-Sanomat suggested: “If you should be unlucky enough not to happen upon a single public summer ruckus, just arrange your own. All you need is a bottle of wine, a piece of lawn and a tolerable singing voice.”

Regional interests were attached to the summer festivals. A pseudonymous writer demanded in Karjalainen in 1977: “We can obtain benefits from the events in the long run, too. The emphasis should be on presenting and developing local businesses and so forth as well as culture. We must use the events to prepare the ground for the municipality’s future.”

In the institutionalized culture sector, the spontaneity of summer festivals aroused wistfulness and envy. Kaleva asked: “Should we not store up the wisdom gained from summer culture and make use of the experience in events at other rimes of the year…?” On Women’s Day, some hankered for a festival of women’s culture, with an umbrella organization of the Finland Festivals type.

The birds of ill omen that once hovered above the festivals had vanished into thin airs. Tatu Tuohikorpi, now press councillor, told Turun Sanomat in 1985 that the goals had been achieved. “Now major newspapers like the New York Times set off on their own accord to find out about our festivals.” He cited Naantali, Savonlinna, Kuhmo and Pori as the most attractive events.

“The positive side of this festival hysteria is its national character and the general enthusiasm”, the pianist Ralf Gothóni sayid. “It is important for culture to be accessible to children and young people even in small villages. The most favourable results will probably only been seen in ten or fifteen years’ time.”

Still, the megalomania of the Finns bothered Gothóni. “Unfortunately I must say that the Finnish cultural summer is much less of an ‘internationally significant’ even than we tend to think. We are not in the centre of the cultural world but on its periphery.”

In 1993, Finland was going through an economic recession. State and municipal subsidies declined, and business no longer sponsored events as eagerly as in the lively ‘90s. Owing to the unfavourable exchange rate of the Finnish mark, a great deal more money had to be allocated to the fees of international performers than before.

In spring 1993, the mood at the festival offices was cautious, sometimes dejected. Bookings did not promise much, although more foreign visitors were coming than in previous years.

By autumn, well over a million people had visited the festivals. Attendance records were broken almost everywhere: there were more sold-out performances than ever before. The Finnish public had accorded culture its generous support.